No Key, No Problem: Vulnerabilities in Master Lock Smart Locks

Published:

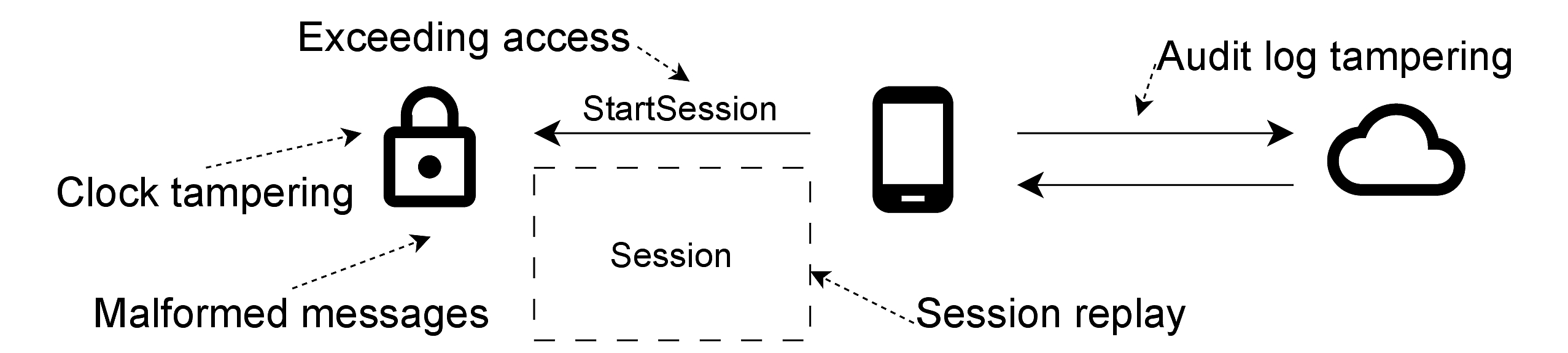

We found five attacks on the Master Lock Deadbolt D1000 that allow the adversary to open the lock without authorization, bypass access revocation, forge log entries, and mount a denial of service attack against authorized users.

Why study smart locks?

Smart locks are increasingly popular due to their convenience and support of additional features compared to traditional locks. By design, these locks are a critical component for access control, such as when they are integrated into the doors of a private home, Airbnb rental, or hotel. Consequently, any attacks on smart locks has a real-world impact on the physical safety of humans.

What attacks did we find?

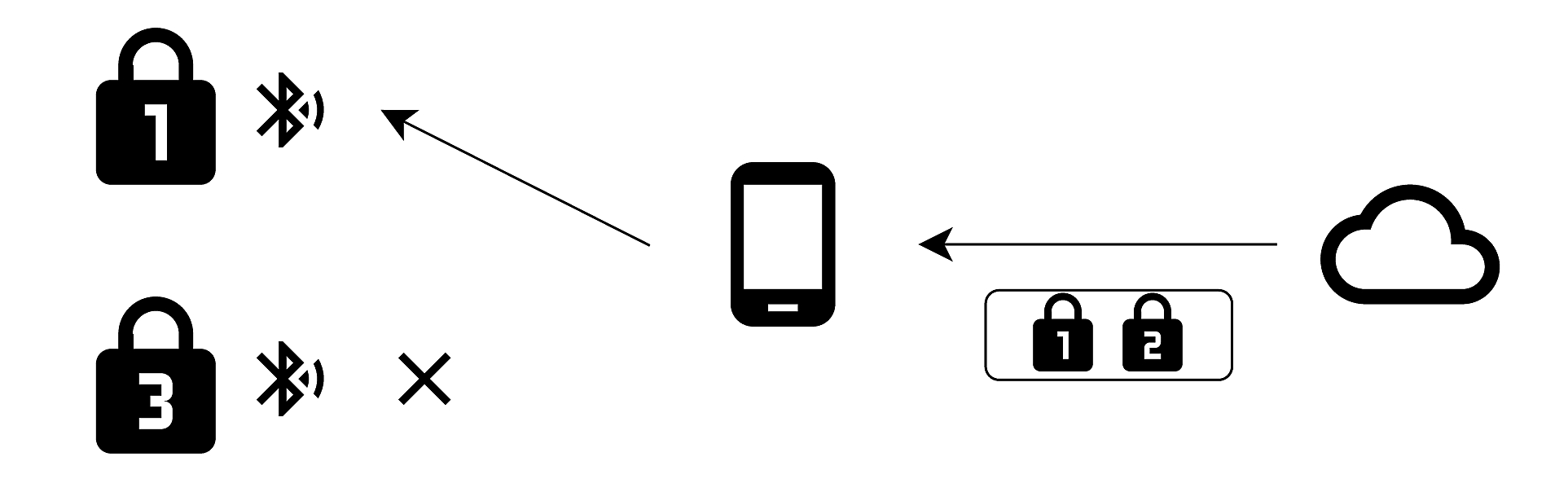

In addition to their security-critical use, smart locks also have an interesting deployment model. The D1000 lock is not connected to WiFi itself to save energy and support offline unlocking. Instead, the lock only communicates with the Master Lock servers over the phone of the person unlocking the lock. This is noteworthy because it implies that the lock cannot synchronize revocation events without relying on the phone, but that phone might belong to an adversary!

Therefore, a complex protocol is needed to support all smart lock use cases, giving many opportunities for attacks. Below, we briefly describe the five attacks that we found on the Master Lock Bluetooth Deadbolt D1000 (firmware version 1679338484).

- Attack 1 (session replay): An adversary in physical proximity of the lock (without ever having a valid account on the lock) can record the Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) communication of a whole session and replay it to repeat all executed commands, including unlocking the lock.

- Attack 2 (exceeding access): Former guests can continue unlocking the lock after their access has been revoked.

- Attack 3 (clock tampering): Malicious guests can adjust the clock time of the smart lock arbitrarily, extending their own access past expiration or locking out all legitimate users.

- Attack 4 (audit log tampering): An adversary that only knows the lock’s identifier (which is advertised over BLE) can upload arbitrary audit events to the telemetry server, and prevent legitimate audit events from being uploaded. Hence, the adversary can hide their own activities.

- Attack 5 (malformed messages): Without valid access, an adversary can send malformed BLE messages to the lock that make it unresponsive or corrupt memory, which results in a Denial of Service (DoS) for authorized users. A malicious authorized user can even leak the memory of the smart lock.

Next, I describe how we pulled off the first two attacks in a bit more detail. The interested reader is encouraged to look at our paper for a more technical description of all attacks and our reverse engineering techniques to overcome Master Lock’s custom obfuscation.

Deep dive 1: authentication and exceeding access

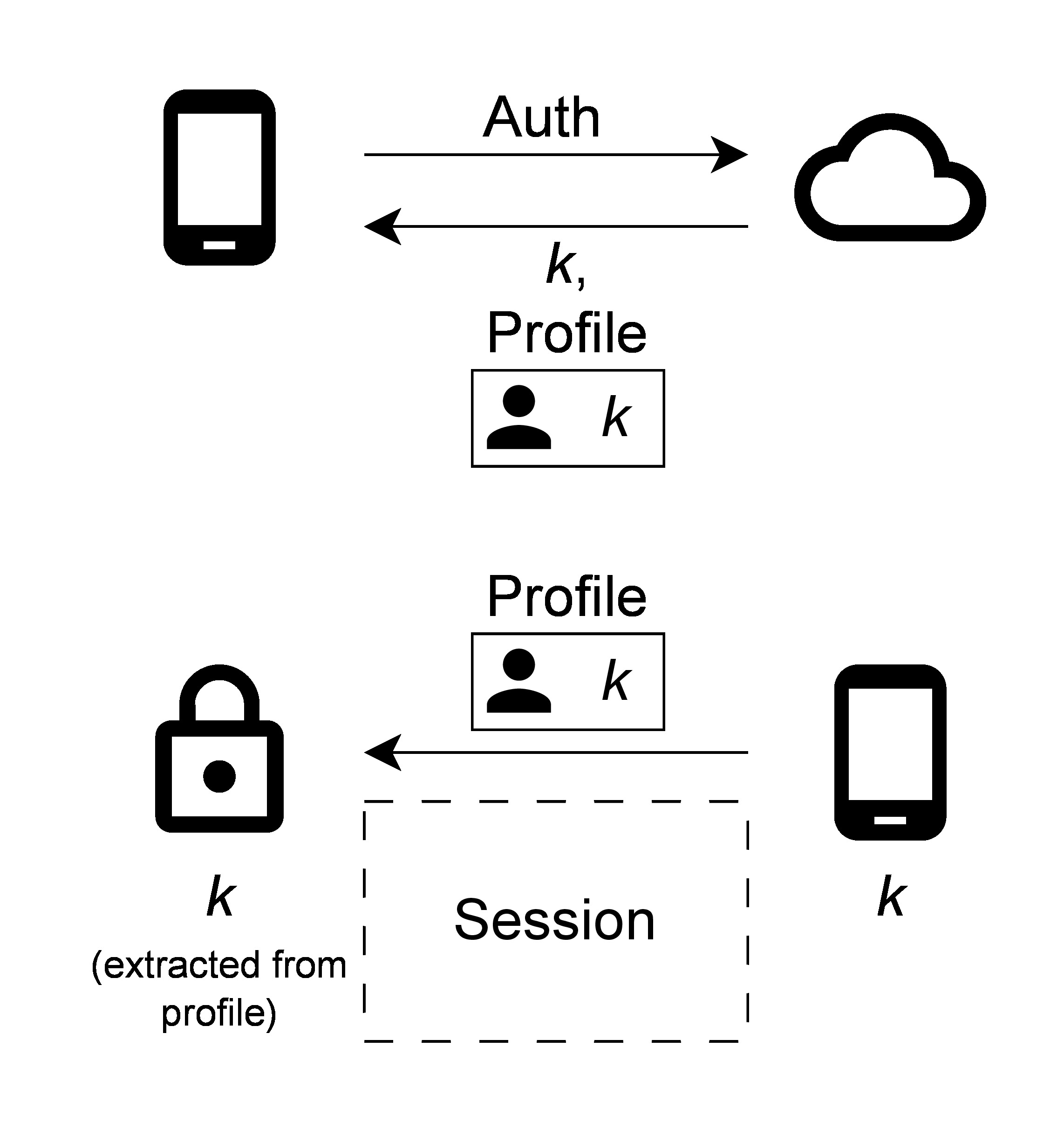

Authenticating to the D1000 smart lock works as follows (illustrated below):

- The user adds their credentials to the Master Lock app, which uses them to authenticate to the Master Lock server.

- Server sends a pair of the session key

kand the opaque profile to the app. The profile contains the same session key and other information, encrypted with a symmetric key that is shared between the lock and the server. - The app then transmits the profile to the lock to start an encrypted session over which it can send commands, e.g., to open the lock.

To revoke the access of a user (e.g., a temporary guest in an Airbnb), the lock administrator can remove that user from an access list that the server keeps. The figure below illustrates that on every login, the app first checks which locks are accessible to the user. Locks that are not available are not shown to the user, even if they are discovered in BLE scans. Moreover, the server also refuses to generate session keys and profiles for locks that the user does not have access to.

How did we bypass this revocation?

Let’s look at this profile that users need for authentication in more detail:

{

"profiles": [

{

"id": 128602,

"accessProfile": "xnd+jiDJpP587jpvhoHT4yS0GU3fnYlGYM5LzIrFQH8=|gLaPSy/n ...

"startsOn": "1970-01-01T00:00:00+00:00",

"expiresOn": "2025-08-02T02:15:17.1199254+00:00",

"refreshThresholdMinutes": 387360

}

]

}

We notice that there is a hardcoded expiration date in the field expiresOn. This field is also encoded in the accessProfile that the app sends to the lock. For the lock, the expiresOn field is the only way to validate a profile.

However, this means that an attacker can save a session key and the corresponding profile, and use them with a custom BLE client to bypass the restrictions imposed by the official app. Thus, this attack allows users to open the lock up to nine months after their access was revoked.

Deep dive 2: session encryption and replay

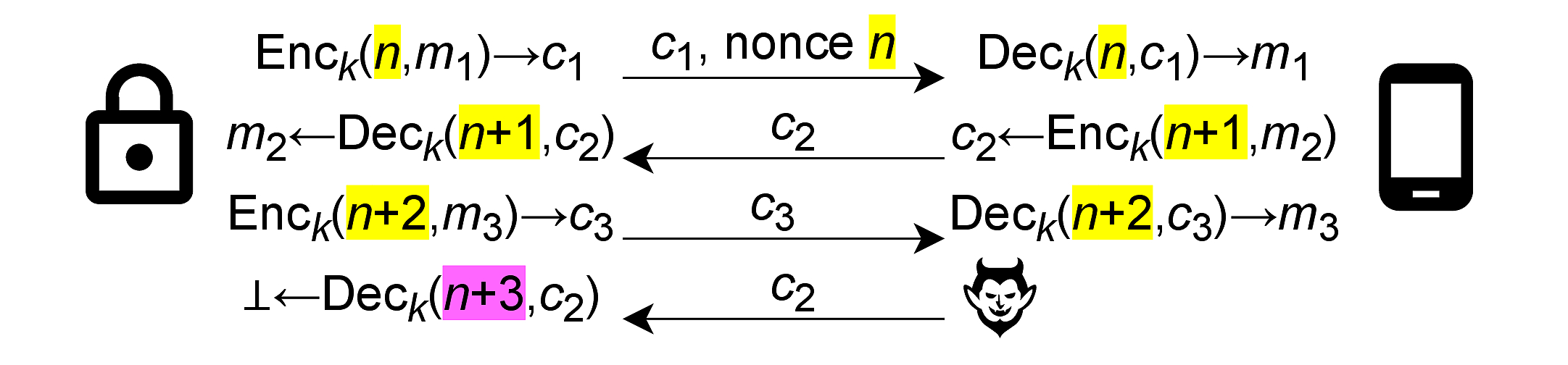

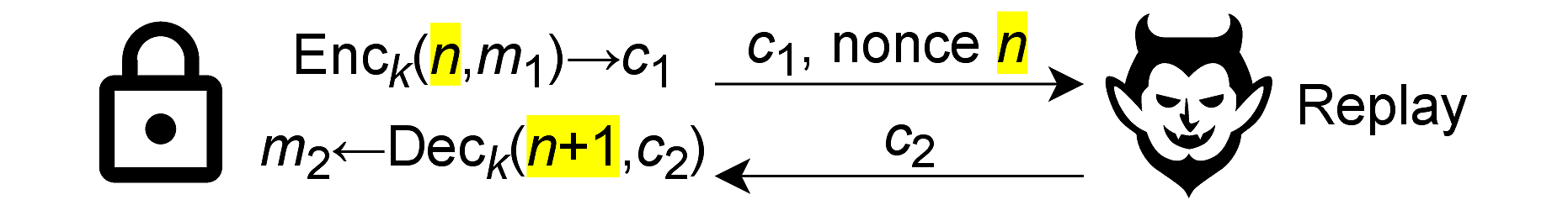

After the app and lock exchange a session key over the previously described profile, they start communicating over a secure channel. For this, they use AES-CCM encryption with an implicitly incremented nonce. The figure below shows an example. First, the lock picks a starting nonce n and encrypts the first message m1, producing ciphertext c1. It sends both values to the app. The app then responds by encrypting message m2 (e.g., an “unlock” command) using the incremented nonce n+1. Here, it no longer sends the nonce because the lock can just increment n.

This prevents an adversary from replaying single messages inside a session. For instance, resending c2 means the lock would now attempt to decrypt it with nonce n+3, which fails.

However, we noticed that the D1000 always sends the same initial nonce n. Therefore, the same messages sent in the same order produce the same ciphertexts. This allows an adversary to replay all ciphertexts in the session until the desired command.

Disclosure and mitigation

We thank the Fortune Brands Connected Products security team for a great disclosure experience. We had an in-depth meeting with their team in which they acknowledged our findings in detail, provided context on the origin of these issues, insights into their design decisions, and updates on the mitigation progress.

For the exceeding access attack discussed in more detail above, Master Lock shared that only the D1000 product had a profile validity period of nine months. This was because they had a firmware bug that previously caused the real-time clock of the D1000 lock to jump forward in time. To avoid locking users out, they increased the validity period.

This firmware bug is already fixed in the D1000 firmware that we targeted. Master Lock plans to push out firmware updates to D1000 locks more aggressively and then reduce the validity period of access profiles to seven days, as in their other products.

For the session replay attack, the lock should choose a fresh random nonce from a cryptographically large space for every session. Master Lock informed us that among their products, only the D1000 firmware resets the nonce when starting connections. They will fix this in a firmware update.

All mitigations are described further in our paper.

Acknowledgements

Nadia and I proposed this topic for the Early Research Scholar Program (ERSP) at UC San Diego. The ERSP introduces second-year undergraduates to research, teaching them everything from reading papers to conducting research. As part of this program, Danielle Dang, Sierra Lira, and Angela Tsai found related work, identified a promising target (the D1000), and started setting up the Bluetooth sniffer and prodding the communication protocol.

Towards the end of the ERSP project, when it was clear that we needed a non-blackbox understanding of the protocol, Chengsong—then a master student—joined and reverse-engineered the Android application, which then allowed us to find the attacks.

I myself am grateful for being supported by a Google PhD fellowship, which gives me the freedom to pursue projects like this one that help undergrads and master’s students get into research.

Further Resources

Our paper is available here.